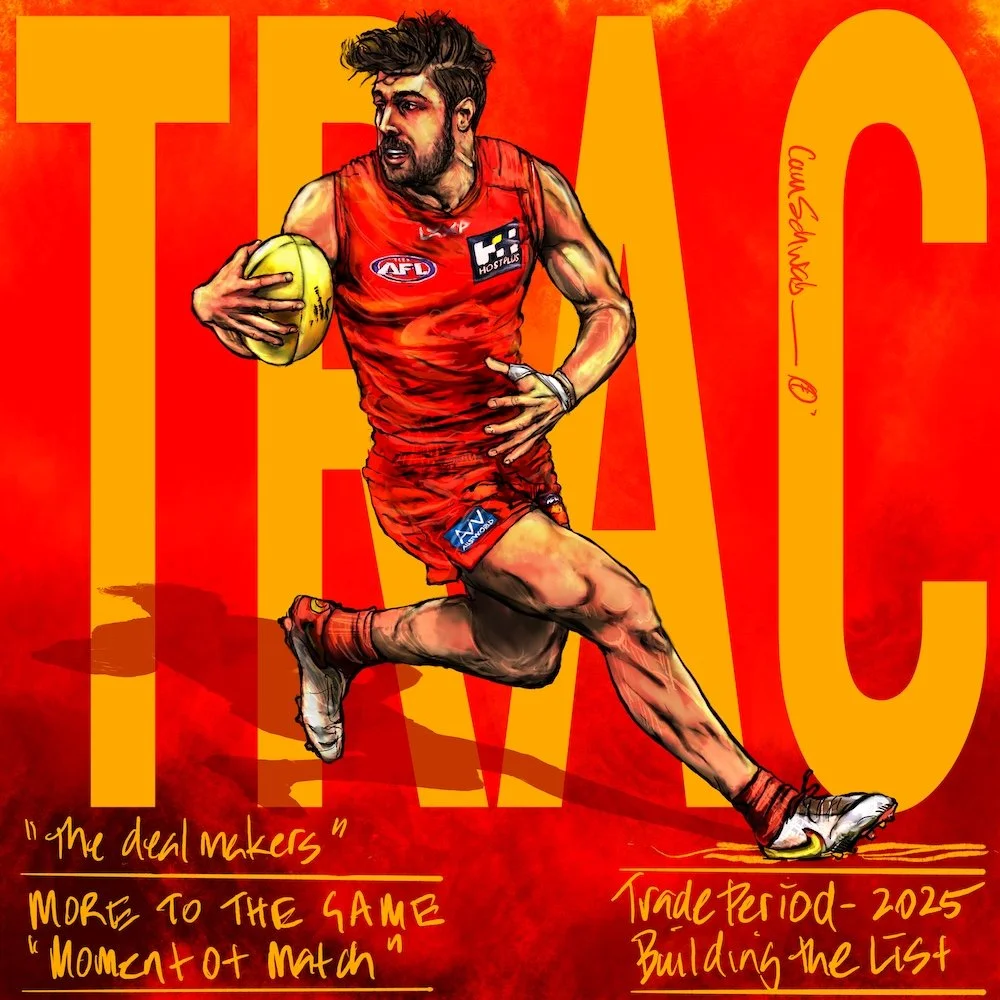

Trade Period - The deal makers

Christian Petracca is now a Gold Coast Sun

Whilst the future will tell its own story, the leaders at the Suns who have been driving this process are crystal clear, and it seems that Christian Petracca understands what he brings and how he can make himself invaluable to the club and its vision.

Growing up with the game, the most high-profile and respected football leaders of this time were the deal-makers.

They were legendary figures; their folklore was as influential a part of my football education as the players they recruited.

One of the most famous stories related to Royce Hart, a champion Richmond player and my first childhood hero, who signed with the Tigers as a seventeen-year-old Tasmanian for the price of a suit and a few Pelaco shirts. It was a deal negotiated by the most legendary Richmond deal-maker, club Secretary Graeme Richmond.

______________________________________________

My father, Alan Schwab, would likewise build a reputation as a shrewd deal-maker.

He was also a key figure in the great Richmond era as the club Secretary, managing to step out of the significant shadow of his predecessor, Graeme Richmond. They would do enough deals between them to win the club five Premierships.

I grew up with these football deal-maker stories and loved them. Dad would scour the country for the next great Richmond player, following up the tips and leads from his multi-layered network of contacts who would feed him information on likely prospects playing in country and interstate leagues.

I remember him embarking on these trips, leaving our Mt Waverley home, pointing his Holden Kingswood in the direction of a small Mallee town, arriving seven hours later to sign a young footballer, and driving home with the paperwork feeling like a winner.

He’d tell me about these players, painting word pictures so vivid that I could see the player performing acts of raw, unfettered football mastery on dusty country football grounds. And then, a few short years later, that same player was doing a lap of honour with his Tiger teammates on the MCG, carrying around Premiership silverware.

For this football love-struck kid, it was intoxicating stuff.

When he went recruiting in Tasmania, I remember asking, “Can you bring home another Royce Hart?” His response has stayed with me. “You only get one of them in a lifetime,“ he said, but he did sign a great Tiger, Michael Roach, who would kick a century of goals in a Premiership four years later.

Our summer family holidays were organised around such trips, though I didn't understand that at the time. I grew up thinking all families went to places like Pyramid Hill and Mildura for the summer break.

There was one year, the first time I’d ever been on a plane, we went to Adelaide. It was a serious step up from our previous country jaunts. The trip recently came up in a conversation with my mum, Annette, who explained we were there because Dad was trying to sign a red-headed Woodville SANFL ruckman by the name of Craig McKellar, who, a couple of years later, would get to do one of those laps of the MCG as a Tiger premiership player.

______

There is a famous trade deal my father landed, which might be considered the game’s greatest ever, securing his place in the annals of deal-maker lore.

It was so big that I have no idea how it started or finished.

The Tigers swapped their two-time Premiership player, Billy Barrot, a dynamic centreman loved by the Tiger faithful, for St Kilda dual Brownlow Medalist Ian Stewart. The following year, Ian Stewart won his third Brownlow, becoming one of only four players in the game’s history to achieve this. Billy Barrot played only two games for St Kilda.

When Richmond named its ‘Team of the Century’ three decades later, both Stewart and Barrot were in the team.

There was great intrigue surrounding the deal, and it seems, a fair amount of ‘skullduggery’, a term that brings some honour to the lying, cheating and ‘gamesmanship’ required to facilitate a deal of this nature, but also a celebrated part of the game.

During this era, Richmond wore its success, aggression and ruthlessness like a suit of armour. The supporters of all other clubs seemed united in their disdain for Richmond, and the Tigers promoted and thrived in this conspiratorial ‘us against them’ world of their creation.

Richmond single-mindedly, unrelentingly and unapologetically sought to shape the competition for its benefit and, in doing so, built a formidable club.

It was a Tiger era of success that paled all of the club’s historical achievements and the marker from which all future teams and efforts would be calibrated.

______

It was also a period when the club built a reputation for letting nothing stand in the way of its success.

A conversation with any Tiger supporter who experienced this era will not only focus on the fact that Richmond teams won, and often, but also on how they went about winning, and everyone went with it. No apologies needed or expected.

Pure intimidation was at the heart of the Richmond playbook, a psyche not restricted to the field of play; it permeated every aspect of the club.

Behaviours drive culture, and culture embeds behaviours, so it was at Richmond.

No one was immune. If you were a player considered not to have any value, or a use-by date was imminent, or the imperfect football market gave you a higher perceived value than your club, you were discarded, packaged, bundled off and traded. Few, if any, were protected from this potential or possibility, no matter your contribution, track record or team glory you shared.

Nothing got in the way, be it an opposition player who stood between a Richmond player and the ball, or the rules that governed the game, anything impeding the club and its ambitions to see a player in Richmond colours, or more particularly, not in the colours of teams who were most likely to rival the Tigers at the pointy end of the season.

The focus was not merely on making Richmond better but on diminishing and reducing their opposition.

A recruiting endeavour was an opportunity to hold power over clubs and competition, and there were lashings of ego in this process. It was arrogant, hairy-chested machismo. The stakes were high, and with this mindset, it was inevitable that deals would not always go to plan, with disastrous, far-reaching outcomes, the protagonists blind to this possibility.

And so it was for Richmond.

______

The Tigers had just won back-to-back Premierships and became obsessed with signing a South Melbourne player, John Pitura, to replace the ageing Ian Stewart.

Richmond’s keen interest in Pitura started when he was selected in the Victorian State team, a significant honour, but became an obsession when he performed well against Tiger champion Francis Bourke, a player who rarely lowered his colours.

Pitura’s team, South Melbourne, was a lowly club, winning just here and there, while Richmond was enjoying an era to rejoice. In the minds of the Tigers, a club like South Melbourne was just a road bump between them and their quarry.

But the Tigers’ fixation was there for everyone to see. There would be no art in this deal. They were at their bully-boy best, or worst, and they overcommitted on the deal as the club choked on its hubris.

Richmond massively overpaid for what turned out to be an overvalued asset. They traded three players, one loved veteran and Premiership ruckman Brian ‘The Whale’ Roberts and two youngsters who had played a dozen games between them, 19-year-old forward/ruckman Graham Teasdale and 20-year-old half-back Francis Jackson. There was also a significant amount of cash, undisclosed at the time.

Not only did the Tigers lose valuable young talent, players who were the product of their previous recruiting efforts, but they also crushed their culture, the deal becoming a tipping point.

______

I am sure if John Pitura had starred and become the next Ian Stewart, as was the hope, the deal would have had different consequences.

Pitura was beautifully talented, balanced in the way many left-footed athletes are, and with a thumping and pinpoint kick to match. A handsome athlete, who always seemed to be sporting a suntan, even in the depths of the Melbourne winter, somehow he just didn’t seem to fit, never making an impact, and left after three seasons of inconsistent football.

The former Swan was in the wrong pond.

Meanwhile, the players the Tigers traded thrived in their new environments. ‘The Whale’ Roberts starred in the ruck for the Swans, Graham Teasdale won the Brownlow Medal two years later, and Francis Jackson became a mainstay of the South Melbourne defence for the next decade.

Soon, even the Tiger supporters turned on Pitura, unfairly, as it was never his fault that the trade played out the way it did. All he wanted was to play in a successful team, perfectly reasonable after slogging away at a lowly club for 100 games. He became a lightning rod of supporter wrath as the club began to decline.

The deal was spoken of as the beginning of the near end when the club found itself on the brink of bankruptcy and last on the ladder only a decade later.

______

The irony, if that is the correct word, is that I was now the CEO of the Tigers, trying to resurrect the great club, that decade later.

There were countless occasions, in moments of reflection on how dramatic the club’s fall had been, when people would say of the demise, “It all started with the Pitura deal.” It was hard to argue against their contention, even understanding the role my father played.

With this lived experience, you’d think I’d know better. But no, I still wanted to be part of this action, and throughout my thirty-year career in the game, I was mostly an active player in the player trade market.

Being one of those football deal-makers had become an unspoken personal goal, something I saw as a key to my future in the game, and perhaps the opportunity to one day write myself into the next generation of deal-making folklore.

______

This process is now far more structured, known as “Trade Period”, and the 2025 edition came and went, just weeks after the Premiership had been won and lost.

The Trade Period has long become an event in its own right. At a time of year when community sporting interests should have turned to cricket, tennis and horse racing, the speculation and intrigue of the Trade Period dominates the sporting media, even more than any week in the season itself.

It perversely makes sense.

Football lives on hope, and Trade Week represents the ‘Season of Hope’.

As the season plays out for clubs and their supporters, most experience the dissolution of hope as their teams fail to compete and are unlikely to feature that year. Then the season finishes, and the Trade Period commences, hope renews. If your club is active, it talks to its ambition and efforts to improve its playing stocks, while providing the opportunity to judge the capability of those with their hands on the trading levers as deal-makers. Reputations are at stake.

Having participated in over twenty Trade Periods, I’ve experienced some of the worst behaviours of otherwise decent and clear-headed people, and I was often in the middle of this mud heap. I have been part of shouting matches with usually sensible people, reduced to name-calling, threatening, trying to hold power over each other, allowing it to get personal, but in doing so, creating a stalemate where the deal cannot go anywhere because our respective egos would not allow it.

The happenings of Trade Week are amplified by an obsessive media, hanging on any morsel of information to be first with the latest, even by seconds. It is a major media event, with Trade Radio at its heart. Not content to follow the story, they fight each other to lead it, and when there is nothing left to talk about, they create it, make it up, scenarios created, mostly improbable and impossible, but it keeps the content churning and the people listening, particularly during the inevitable quiet periods.

It is not a passive process. The media are major players in this chaos. Often used by player managers and club people, fed selective information to help position their player or club in a possible deal by putting public pressure on the parties to get the deal done, even playing to the fears and insecurities of the deal-makers in this high-stakes environment.

It is a petri dish of human behaviour, and will often bring out the worst in competitive, proud, ambitious people, who are generally used to getting their way but are now panicking and skittish as the clock ticks down with deals deadlocked.

While some of the footballers are active in this process to facilitate their aspirations, as they should, often they become fodder for the ambitions of clubs, who somehow justify setting aside every team-based value they have endeavoured to embed for the other fifty weeks of the year, and behave like arseholes, and I did.

Days have ended, some of the longest and most frustrating of my working life, and I am in the car driving home, and a voice in my head asks, “What the fuck were you thinking?”

I know the answer.

I wasn’t thinking; I was feeling, mostly overwhelmed, allowing my emotional state to drive my behaviours, when the role I played, the leadership position I held, expected more.

I look back and shake my head.

Yes, some trades created good outcomes, others did not, and some followed me for the rest of my life. Every Trade Period, pundits judge the merits of deals past, all with the wisdom of hindsight and never with the context of time, place or circumstances. But, my reflections are not the success or failure of the deals I facilitated, perceived or otherwise, but my behaviours at the time.

Was I showing my true colours in these moments, modelling something very different to the behaviours I espoused every other week? Perhaps the Trade Period wasn’t making who I was; it was revealing who I was, and I had work to do.

It was not about my capacity to negotiate; it was much more profound, going to the heart of what I bring as a leader.

______

I needed to work on my inner leadership game to enable the outer leadership game I had worked so hard on for so long.

As leaders, we are measured by how we show up, the consistent application of an ethos and mindset aligned to an agreed vision and a set of values, with the skills and fortitude to execute individually and as teams.

It is the ‘Leadership Promise’, a mostly unstated pledge or oath that leaders take when they assume the role, not always understood but a core expectation of leadership, and, in my experience, the most common reason leaders fail.

The expectations are both explicit and understood, but mostly unspoken, reflected in how people experience you, remembering that people do not experience your intentions; they experience your behaviours.

It is a promise that is relatively easy when it’s business as usual, but in my experience, leadership is rarely that. Leadership is only needed when the world gets complex and messy, which is often, and the reason why leadership is needed and when it matters.

The Trade Period is everything that makes leadership hard. It is cognitively challenging, given its many moving parts and complex rules. It is emotionally stressful as we are dealing with people’s careers and lives. There is the pressure of a high-risk, high-stakes endeavour with the capacity to heavily influence the club's short and long-term success, amplified by the minute-by-minute, blow-by-blow scrutiny and judgement of a media beast with its agendas and expectations.

But somehow, it seemed even more. It felt like your identity within the sport was on the line, at least that was the story I was telling myself, something I am more convinced of as I write this.

My first thought was, “I need to be more disciplined?” I tried that with some success, but my behaviour lapsed too often to claim any ingrained behavioural change, and I was soon dealing with that same inner voice.

I started thinking of leadership as a craft, particularly in challenging times and situations, including tough negotiations. Anyone seeking to master a craft needs a system. “We do not rise to the level of our goals”, James Clear says, “We fall to the level of our systems”.

I realised I needed a system. A circuit breaker between how I felt in the moment to enable clarity of thought to inform how I best behave, allowing an outcome to emerge and evolve, not some predetermined expectation.

As Dan Gregory says, “Design beats discipline”.

So I designed a system.

When I feel any form of emotion or uncertainty kick in, be it a testy meeting, a negotiation, or a difficult conversation, I pause and pick up a pen or pencil, preferably the fountain pen gifted many years ago that I have carried with me for most of my career. This pen requires a more deliberate process; it slows me down. I then open my Moleskine Journal to an entirely new page, and I write at the top of the page:

“As CEO of the [Insert Name] Football Club, what does this situation expect of me?”

I then write four words:

Calm

Brave

Humble

Kind

Under each word, I would start writing down a sentence, which quickly becomes a short paragraph of now connected thoughts, a far more cohesive and trustworthy story to tell myself, linking back to the bigger picture of what I am there to do.

It might all seem a tad pretentious, a bit over the top, which is not an accident. There is symbolism in the pen and paper, as well as an embedding of the ritual to pause, slow down, and take a breath, since your first thought is unlikely to be your best thought.

Velocity is never the answer to complexity.

A core challenge of leadership is distinguishing what truly matters from what seems to matter. The seems to matter is often making a racket, demanding our attention, telling us it’s urgent, distracting us from what truly matters.

It is an exercise in sense-making in the face of ambiguity, uncertainty and conflict, not allowing momentum to influence your thinking.

In the Trade Period, a response might read something like:

Calm: Am I clear-headed? Take a breath, listen and watch. What are they really saying here? Look for signs. Stop talking! Allow space in the conversation, and let them fill it. Ask ‘What?’ and ‘How?’ questions. What other deals are they trying to make happen? How can we help them? Something we might not value that might be valuable to them. Try to work out what they need from this deal.

Brave: Don’t let this deal compromise our values or our future. The courageous thing might be to walk away now, even though we have put months into this deal. That’s ok. We live and learn. There is no shame in that. There is no such thing as a sunk cost. Don’t over-commit, or kick the can down the road by overcommitting, otherwise, it will bite us. Don’t let public opinion create an expectation we feel bound by. We know what we are doing. Trust our insight. Recognise when a good deal becomes a bad deal. Adopting this position will help us determine how committed the other parties are and whether they have other options.

Humble: How are people experiencing me now? It is not about me. I don’t have the answers; drive an environment of creativity, making the best of our collective imaginations. It is never about me. Don’t personalise it. Keep that ego in the jar and the lid on tight! Be kind. Be decent. Stay true.

Kind: To be compassionate. Drawing on ideas of fairness, even in these high-stakes environments. Start with yourself. Often, self-compassion is what is needed.

I like to say, “I don’t teach anything I haven’t fucked up”, and this is what I have learned. It does not guarantee a successful outcome but gives it a chance.

______

Christian Petracca is now a Gold Coast Sun.

When he won the Norm Smith Medal as the Demons won their first Premiership in 57 years in 2021, he etched his place in the folklore of the game’s oldest club.

That same year, the Suns finished sixteenth.

It would have been unthinkable at the time that the Demon champ would be playing for the Suns five years later.

But the work was well underway at Gold Coast.

Collecting talent is different from building a team. Yes, the goal is to build a team, but collecting the right talent comes first, and the Suns were doing so in a way only they could.

Their way was judged harshly because it did not meet many of the accepted ‘norms’ of the trading process.

They had tried the accepted way, and it had failed, as they watched their best young talent playing in Premierships elsewhere, such as Dion Prestia and Tom Lynch at Richmond.

From our constraints come our opportunities, and so it is for the Gold Coast Suns.

People assessing the trading and list-building process think of it like Super Coach, a kind of fantasy league.

Bill Belichick, the legendary New England Patriots Coach who did this better than anyone and has six Super Bowl rings as evidence, describes it in all of its nuance and complexity:

“Roster construction involves managing the push and pull of how individuals fit into groups, how groups can serve individuals, and how everyone can serve a common goal.”

The Suns were always building a team, the push and the pull, even though it did not always look that way. But in 2025, the club made the finals for the first time, and now the football world sees it.

Christian Petracca, one of the game's best, sees it, and what a wonderful opportunity for both player and club.

I will finish with another Belichick insight:

“Good roster construction is a tricky balance between the overall team vision and the people who must carry out that vision. One cannot work without the other. If you are a leader, you manage that balance by scouting and developing talent that matches the vision. If you are a member of the team, you must understand how you fit in, be honest about what your own strengths are, and find ways to make yourself invaluable to the overall vision.”

Whilst the future will tell its own story, the leaders at the Suns who have been driving this process are crystal clear, and it seems that Christian Petracca understands what he brings and how he can make himself invaluable to the club and its vision.

Play on!

My work builds on the belief that leadership is the defining characteristic of every great organisation or team.

You cannot outperform your leadership.

Our offering is designed for leaders who know that personal leadership effectiveness drives team and organisational performance and that there must be a better, more efficient and effective way to learn leadership.

Feel free to connect, or make contact